On Band and Business

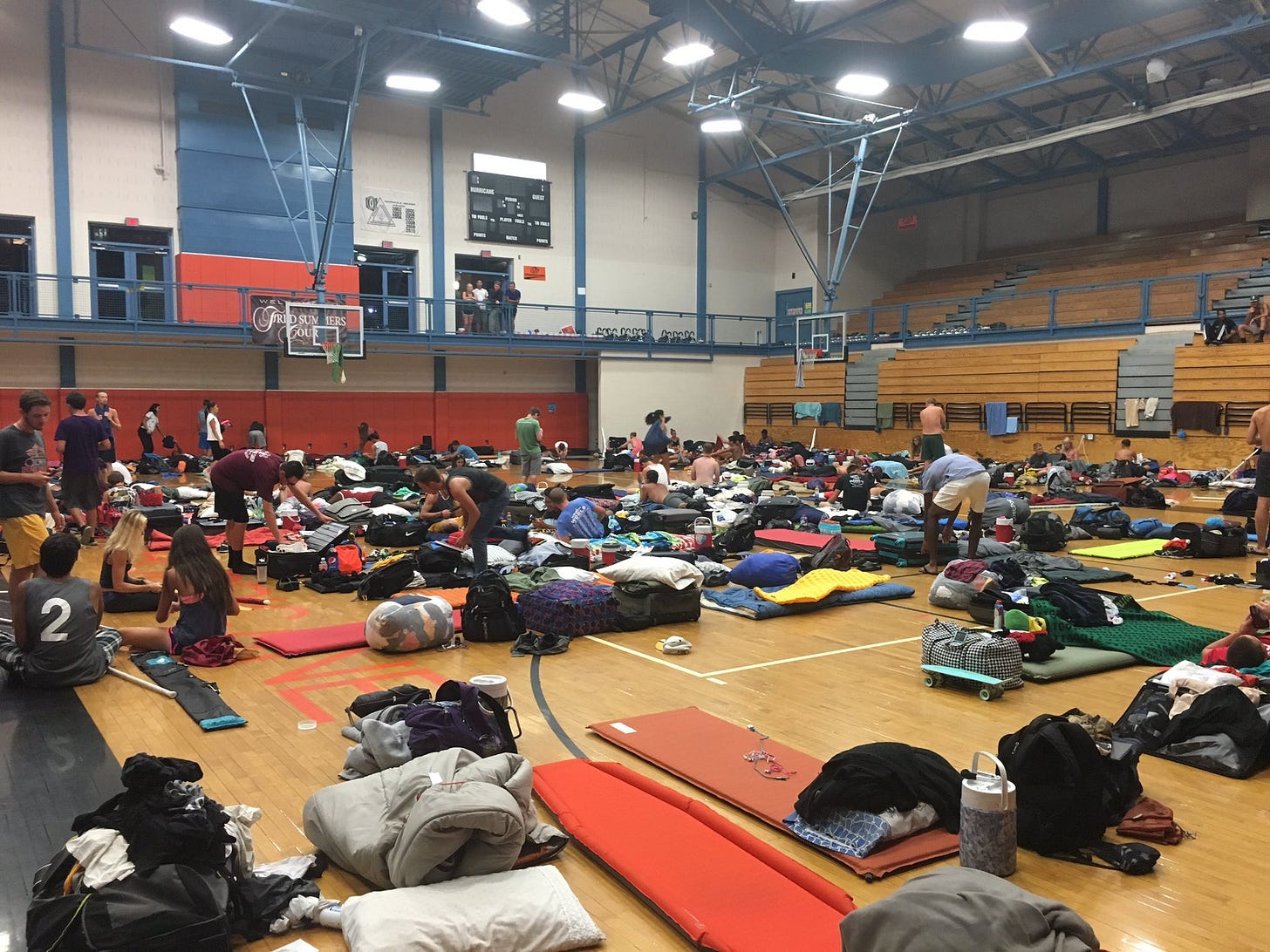

Every day during the summer, a group of 165 young performers wake up in a high school gym on air mattresses. After they get up, their breakfast (the first of four meals a day) is served by dozens of volunteers out of a catering semi-truck parked outside as they prepare for rehearsal. It's a non-stop schedule for nearly three months with a typical day that looks like:

8am: breakfast

9am: visual rehearsal

12pm: lunch

1pm: music rehearsal

5pm: dinner

6pm: ensemble rehearsal

9:40pm: show run-through

10pm: snack

11pm: lights out

The group only had 4 hours of floor time last night – that is, sleeping horizontally. 6 hours of their night was spent on one of the 6 tour buses they've traveled over 5,000 miles on at this point in the season.

A hefty percentage of the summer season is spent in transit on a bus. Members spend so much time on their busses that they will make them into a studio apartment. Square footage: 2 feet by 2 feet. They'll even stick a bathroom caddy to the window to give them shelf space for the long-hauls members undergo. They get comfy, because a season consists of at least 15 contests in different towns across the United States. And the busses smell like nothing you have ever smelled before in your life.

Today is a routine morning for a group competing in the Drum Corps International (DCI) season. DCI is a summer activity that concludes with finals at Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis, Indiana. The tag line of the activity is "Marching music's major league" – and it has been ongoing since the 1970s. It's a physical and creative activity that members from the age of 16-22 audition for to earn a spot.

Each of their shows are judged, scored, and expected to be better than the last time they performed it. Parents, friends, and enthusiasts cram into stadium stands on humid nights waiting for their favorite group to throw down a show. They are in the stands asking for mild tinnitus – and the drum corps' members happily give it to them. After their scores are announced, the busses and equipment trucks are once again loaded up to head to their next destination in the middle of the night.

But for a rehearsal day like today the only goal is improving their score. Today this group needs to fix an unmissable "tear" that keeps happening in their closer, make some adjustments to music, and get a few more reps in of the entire performance.

As members finish breakfast, they'll start the trek for rehearsal. By 8:50am members will have grabbed their equipment (instruments, flags, drums, etc), water jug, sunscreen, and hunt for the football field in the unknown school. Public schools are a cost-effective way for a drum corps to house the members for the summer season – and they need at least one football field. Operating a drum corps requires being extremely cost aware as it is a capital intense activity, with few ways to generate revenue.

At 8:59am the young performers within the hornline will set up, elbow to elbow in an arc shape, instruments pointed at the horn sergeant, shoulders back, standing perfectly straight, feet angled at 45 degrees, fingers curled over the valves, looking towards the center to make sure their spacing is the same between the nearly 70 horn members.

The horn sergeant, usually a member in at least their 3rd season shouts a rhythmic "Ready... front!" and the members snap their heads forward, and then their horns down in front of their chest. It's 9am, and their rehearsal has officially started.

Why did I write this?

The cost-benefit analysis of sleeping on a gym floor, traveling by bus, showering with your peers, and rehearsing during the hottest months of the year is admittedly insane. To the members, though, it's worth every single penny. These young members are paying to get sunburned, play music, toss flags, and make shapes on a football field. And I myself would not be where I am if I hadn't done the activity.

The last 7 years I’ve been building and running FireHydrant and the more I realize how many lessons could be extracted from DCI. Because DCI is a masterclass in organizational alignment and execution.

On Band: Pre-Tour

Before the DCI season even begins the show music and drill (shapes on the field) has been designed and written. There will be edits as the season progresses and feedback emerges, but for the most part the music, the visual, and the show design will stay the same for the entirety of the summer and receiving a new score each performance.

For a corps to increase their score – they need to increase their risk and execution. A 120 beats per minute tempo while playing simple notes and moving a few feet? Piece of cake. Running and playing Metropolis 1927 at 184 tempo as a closer perfectly? That's how you win.. But to increase execution, the corps needs to immerse themselves for several weeks to get started. Enter: Pre-tour.

Pre-tour is when the corps goes all-in on learning and rehearsing their show. Corps members spend every day learning their show for upwards of three weeks with no public performance. Members say goodbye to their loved ones and lock themselves away for the hardest part of their season. They can expect a few sunburns, sore knees, and harsh but fair feedback from the staff. The show memorization process starts on day 1 with every member getting their first "dots" on the football field.

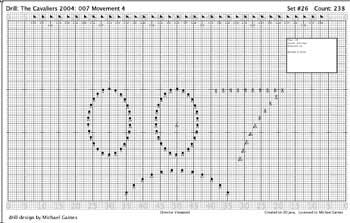

Dots are what make a band a marching band. A dot, put simply, is a coordinate on the field. Dots are the "longitude and latitude" of marching band and DCI shows. It details to every performer where they need to be, at what count of the show, and how many steps they must take to get there. By stringing together sets of dots, you get the well-known shapes and effects that marching bands create called “drill.” If you can imagine a huge sheet of graph paper over a football field – that's how dots work.

It's not possible to memorize a dot on the first try. Members will write down their dots, any notes, and reset multiple times during rehearsal to remember two measly sets before learning the next one. A single rehearsal might allow the corps to learn 10-15 dots. The most competitive shows will have over 200 sets members must learn.

Once learning drill has built momentum within the corps – they start cooking with gas very quickly.

On Business: Routes and Roadmaps

In business there are three terms that all vaguely resemble each other. Businesses typically have a mission statement, a vision, and a product roadmap. In my eyes, they're all different phrases to help explain the same thing: Where we are right now, and what are we doing next to get to where we want to go.

For example, FireHydrant's vision is to help businesses build more reliable software. We have a roadmap that helps us know the route we are taking to achieve that, and several fiscal and quarterly goals that define the boundaries of the current mission. You can ask any member of the FireHydrant team what our fiscal year goals are right now, and they'd be able to tell you without hesitation.

But getting there was not an overnight achievement. Before we started this fiscal year (FY26 for us) we planned, and planned some more. We had a pre-tour for ourselves.

In essence, the leadership team was responsible for drawing the sets of drill that the rest of the organization will ultimately "perform" with. We know that for us to hit a large release effectively, we need to maneuver our engineering team into a position where they can deliver results with exceptional execution. We focused on what we wanted to achieve, and who we wanted to achieve it with.

A significant portion of my job as CEO is repeating our goals and current mission in various ways – the drill of our company. Because, as with band, it's impossible for anyone on our team to recite it after hearing it for the first time. I need to visualize what dots need to be drawn on the imaginary field our business is playing on – and make sure everyone else knows them, really knows them, too.

Because it's not enough to give a Google Slides presentation about what is up ahead while ending with “Ready, set, go!” Humans can't retain complex information on the first try – and need to hear it repeated over and over again for it to truly stick. Eventually, when everyone knows their drill, only then you can start cranking up the tempo.

On Band: Tempo

When performers take the field for competition they've already rehearsed for hundreds of hours and have earned their spot to be on the field. When a show is about to start, the most important thing every member needs to internalize is their tempo. If members start their show with the wrong tempo, they will (quite literally) be off on the wrong foot.

During rehearsals, educational staff will use mild torture by blasting a beat into the ears of every member of the corps during rehearsal. The machine is called (and this isn't a joke) "Dr. Beat." I can still hear it to this day over 13 years later. But there's good reason for it.

Tempo is the life force of a show. Performers are taught to link their foot steps to the conducting hands of the person on the podium: the Drum Major. The tempo on the field at any moment is set by the podium's hands, but it is also amplified and aligned further to the steps of the center snare (the snare that is always in the middle of the 8 other snare players). Without a drum major, there isn't a tempo.

For all 165 performers to know the tempo, there's a staring competition between the center snare player and the drum major. The visual tempo of the drum major's hands is amplified by the percussion section of the corps – a group that every member can hear at all times. The drum line’s drill is commonly located behind the corps on the field to achieve this as well. This means the hornline and color guard see the drum majors hands in the front, and hear the drum line behind them. This enables "vertical alignment" to the music and visual movement: perfectly synchronized harmonies and foot steps. However, when the drum major's hands are not aligned with the snare players or worse – the entire corps – terrible things can happen, like a tear.

A "tear" is a nasty moment in a drum corps performance, and it's hard to miss in the judges box. If the horns are suddenly 1 beat behind during a tempo change from the drum line, the flags, pit orchestra, rifle line, and drum line will hit a big show moment a ahead of time. It's a jarring experience for the audience, and it impacts the score the corps will receive from the judges. Most corps can self-correct a tear mid-show by realigning to the drum major's conducting, and a fast correction can mitigate a large impact.

But a really bad tear – one that goes on for a few bars of music – can drag the entire energy of the performance down. The moment a corps finishes their last set – every member knows what kind of a show they just had. They can feel it as the reverberations of their last note fade along with the applause of the audience.

In a business, this is no different. Every team member knows when the business has its own version of a tear.

On Business: Operating Rhythm

As the CEO of FireHydrant, I'm the drum major of the organization. My job is to make sure everyone knows what we are doing, when we are doing it, and how fast we are going to do it. The tempo I set needs to be matched by every team member, or we'll have the same score-killing tear.

The tempo I give to my team also needs weeks of preparation in tandem with the organization's leaders. If my leadership team has no idea what their next tempo is – or they make one up, our whole company rips apart. A tear in drum corps might mean less points, but a tear in a startup means you go out of business.

I feel that it's necessary to clarify one thing: Operating rhythm is not our goals. Tempo is a function of taking how long we have, and how many things we need to accomplish. For example, If we need 1000 new logos in a fiscal year, our tempo is roughly (using a linear scale) 19 logos a week. The importance of maintaining that tempo is also important. It's why we have an all-hands every month – it's the downbeat that ensures everyone is marching on the same foot.

If people aren't using the same tempo in their work as their counterparts in other departments – it gets messy. Because when engineering is building a feature but it falls behind and sales has been preparing to sell that new feature for its release – that's a tear. If marketing is using a new messaging framework but sales is using the old one in demos, that's a tear. If we tell the entire business we have 8 weeks to ship a feature, but then change the expectation to 6 weeks – you guessed it: another tear.

To create an aligned business, I need to have the same staring competition a drum major has with their center snare – but with my executive teammates. If our collective tempos are not locked into each other – the entire company feels it.

On Band: One show

Sometimes I'll accidentally pin someone down into a conversation about Drum Corps. People are polite about it, but a question that comes up consistently is "how many different shows do they put together in a season?" – One.

It's a fair question in the world of viral videos of college bands performing a different show at every home game. 400 Texas college band members on the field making a Mario show is entertaining and perfect for the setting, but the 10 hours it took to learn that show wouldn't make it by drum corps standards.

In a single season, a corps competes with one show. One book of music. And one book of drill. They rehearse the same parts over and over again throughout the summer to increase their execution, and therefore, their score. Earning a higher score eventually becomes less about the edits they make, and instead about how much easier the show becomes because of how well the members know it.

On day one of pre-tour, you are fighting for your life to learn a show. The 200 sets of drill per member is an incredible amount of memorization. Then layer music memorization on top of that, and it's downright super human.

But something amazing happens in the back half of the season: members can perform their show with near muscle memory alone. Over the course of 2.5 months, they become so accustomed to the show that a staff member can make an edit to the music the day of a contest and they'll be able to perform it later that night.

Members also create a unique camaraderie each season for themselves. This one-of-a-kind social fabric of a corps creates an excellence standard that few people ever experience. No one wants to be the member that holds the corps back from earning a medal that season. Everyone is expected to pull their own weight.

And because the show, the theme, and the members stay the same – a corps can execute (and edit) their performance at a higher level through sheer repetition. It's the manifestation of "A river cuts through rock, not because of its power, but because of its persistence." - James N. Watkins.

On Business: Consistency conquers

At FireHydrant – we've had inconsistent seasons in the past (that is my fault, and another post for another time). Roadmaps changed mid quarter, features fell out of thin air, and engineers were building a totally different set of products than what sales is currently selling. When we are locked into one "show" for a season, the momentum builds on itself.

Take Signals – our on-call product we launched last year. We dedicated the entire organization to building Signals over the course of 4 months (not much longer than a DCI season), and built a kick ass on-call product replacement that is taking on incumbents easily. That level of alignment allowed us to close hundreds of thousands in revenue before general availability. As the months went on, minor features that we wanted to add were completed in a single day because we knew the "show" we were working with so well. We had muscle memory of which files contained which features, we had the same tabs open in our browsers, and we knew exactly what each person was responsible for.

When the team is focused on one thing – one single show – it's far easier to build momentum on top of it, instead of switching all of the time. A social fabric also forms, creating a team that can take edits far faster than if we are constantly switching.

The Prize

Throughout the season, a drum corps show takes on a life of its own. We'd give sections nicknames only we knew. We'd carry out odd rituals like running and touching a water tower in the distance when we weren't rehearsing well. We'd stand in the rain rehearsing music that we hadn't nailed down yet. We'd miss weddings, funerals, and graduations while we listened to judges tapes on the bus ride headed to our next gym to sleep in.

There was a common saying we heard in our drum corps that always stuck with me. "The effort is the prize" – my trumpet tech in my last season even had it tattooed on his arm. We knew that our best show would most likely be on a rehearsal day with no audience or judges. It would be just us, some fireflies, and our loyal staff on a warm night in the middle of Pennsylvania. Our final hit would have no crowd’s applause, no scores, and no ceremonies.

It's important to remember that no matter what team you are on – a drum corps or startup or otherwise – that the moments that matter are rarely the ones that have a score. The best features a business builds won't be met with applause, and the hardest won sales deals won't have a medal ceremony. But the team you worked so damn hard with to earn these moments is, in fact, the greatest prize. But it’s also true that the more effort that is put in, the more likely it is you’ll have the receipts in the form of a medal – or an IPO.

Eventually a drum corps show has its last audience. When finals concludes and scores are announced, that show will never be performed ever again. It's the one parallel I could not draw between band and business – and I'm grateful for it, because I don't want to play a last note with FireHydrant.

Not yet.